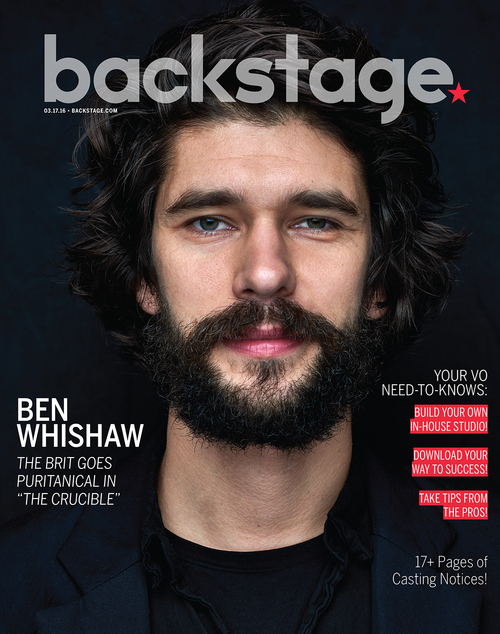

Photo Source: Matt Doyle

Photo Source: Matt DoyleInterview

Remember

Ben Whishaw’s

Name

By Briana Rodriguez

Posted March 16, 2016, 11 a.m.

Ben Whishaw is competing to be heard over the hammering coming from the

Walter Kerr Theatre’s orchestra level. Sitting in the mezzanine, he has to raise his typically subdued voice over the incessant banging as the tech crew finishes construction on the set for

Arthur Miller’s

The Crucible. The stage decor, which director

Ivo van Hove has very consciously had installed piecemeal alongside the play’s performances, is mirroring the cast’s progress; previews are eight days away and they’re five pages shy of the Tony-winning play’s grim culmination. It’ll be the first full run of Whishaw’s Broadway debut.

Playing protagonist

John Proctor, the deeply religious but fallible outsider in a Puritanical community splintered by the Salem witch trials, Whishaw, under van Hove’s guidance, is approaching the production’s cornerstone role with an intuitive looseness. There are no heady discussions about the material and no table reads, just a strict five-hour-a-day rehearsal from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. alongside Oscar nominee

Saoirse Ronan, Tony winner

Sophie Okonedo,

Game of Thrones alum

Ciarán Hinds, and the rest of the 15-actor ensemble.

For Whishaw, the rehearsal process has been an exercise in making discoveries in the moment and uncovering what the play “ought to be” in his respective space.

“Ivo encourages you to not be logical; he’ll say, ‘OK, so this moment you let rip. You push her up against the door and you scream at her, but in the next second you drop that and you’re calm and you’re rational,’ ” Whishaw explains with kinetic hand movements. “So he sort of gives you something, a sphere to play in, but it’s not psychological…. Because if you come at this play like, ‘I’m going to make this a coherent interpretation,’ you smooth it out, you iron out the weird contradictions and jumps.”

John’s termination of his illicit affair with young

Abigail (Ronan) sets

The Crucible in motion and triggers a vengeance plot with accusations of witchcraft flying at dozens of townspeople, including John’s wife,

Elizabeth (Okonedo).

For Whishaw, who adamantly does not subscribe to a specific acting method (“No, I really, really don’t. No.”), the contradictions of Salem’s residents were his jumping-off point for the play, which is loosely based on the notorious 17th-century trials. Examining people who so deeply rely on each other for survival yet are killing each other over little more than needles and poppets—plus John’s belief that he’s a good Christian despite his sins—took precedence.

“It’s this thing [Ivo and I] talked briefly about, which is cognitive dissonance—when you have two things that are opposites. They can’t sit together, but nonetheless…” he explains. “One of the first things Ivo said to us was, ‘[

The Crucible is about] people trying to be humane, but in their attempts to be humane they become inhumane.’ There’s a point they cross and they no longer know what they’re doing. And it does become about this sort of fundamentalist mindset that all of the characters are confined by, trapped in.”

Miller used the real-life trials as an allegory for the decades-long communist “witch hunt” that led to hundreds of artists, including the playwright himself, being blacklisted in show business from the late 1940s through the early ’60s. (The McCarthy era, as it’s known, was also the setting for last year’s

Trumbo and the

Coen brothers’ latest,

Hail, Caesar.)

To pull the production into modern times, van Hove has taken it out of the Massachusetts backwoods and into an environment that, much like his previous Miller engagement,

A View From the Bridge, strips away the world’s excess in a way that gives a new sheen to a familiar narrative.

Unlike in

the 1996 film adaptation and countless theatrical productions, traditional Puritan clothing has been replaced with private school uniforms. A gray classroom with a chalkboard that runs nearly the full length of the back wall slowly fills with drawings and words written or scribbled by characters to symbolically chronicle the buildup to the three-hour play’s climax. And the lighting (by set designer

Jan Versweyveld), which oscillates between chilly, hospital white and warm oranges, visually magnifies the ever-present score by

Philip Glass.

Whishaw’s casting is yet another alteration to the play’s standard formula. Where the farmer has in the past been portrayed as a brute force, his rough edges are emotionally and physically softened by Whishaw’s vulnerability and wiry frame.

“When we first really met, he was greedy and hungry for inspiration,” van Hove says of his lead. “I must say, I’m really impressed. He’s there with his colleagues, he’s never selfish, never egocentric. He really wants to tell a story together with everybody and that was already there the first moment I saw him. He’s tender and sweet and at the same time a strong man, which is perfect for John.”

It’s a New Age interpretation of

The Crucible: “These tribal factions and frictions and bullying and accusations and forcing conformity on people,” as Whishaw explains it. “Working with Ivo, it seems like a completely different play again.”

What makes Whishaw an atypical leading man is this inclination to deflect the attention away from himself and onto those around him. And this same ability to seemingly remove himself from the equation is what makes him so compelling to watch as an actor.

In interviews he pauses often, as if to weigh each word and be sure he means what he says, but onstage, he embodies immediate conviction. He moves with purpose and articulates complex emotions about Abigail, his peers, and Elizabeth with little more than a twitch of his fingers.

His particular style has revealed new layers to Hamlet during his performance at the

Old Vic, to

Bob Dylan in the indie film

I’m Not There, to the serial killer

Jean-Baptiste Grenouille in

Perfume, and more recently to stubborn husband

Sonny Watts in

Suffragette and to

Danny on the BBC1[

nope, BBC2!] thriller miniseries

London Spy. But the true mark of both his range and his intangible allure seeping further into the mainstream was his casting as

Q in the

Bond films

Spectre and

Skyfall, and the upcoming

A Hologram for a King, opposite

Tom Hanks. His varying characters make clear he slips easily into someone else’s skin.

When asked how he found John Proctor (he says it wasn’t a physical discovery of a walk or specific vocalization like other roles he’s played), he points to van Hove and to the high school drama teacher who first guided him in the role at age 15. He mentions a book of mug shots he found in a

West Village shop: “They’ve just got this sort of stripped-down quality,” he says of the men. “They’re very pure. Startled, like they’ve been caught.” He praises his co-star, saying, “Sophie does this brilliant thing where she’ll go, ‘Can we just sit down and paraphrase this scene, ’cause I don’t understand?’ ” And Miller for creating someone so surprisingly familiar.

“It’s something I feel in my own life,” he says, “John’s frustration, you know? I think that’s something Miller writes a lot about, having this social face and then a private self. Maybe everyone feels that, but as an actor you feel that in a sort of strange, intense way because you’re in public.” He pauses with his head in his hand. Sitting up, he says, “I wish I were… I had more courage to be more outspoken about certain things, or feel less need to conform to certain things. It’s bizarre, these kinds of pressures that inform your life, your behavior. Sometimes you look at them coldly and think, What am I doing? But nonetheless, it’s deeply ingrained.”

The pressure to be an open book with his personal life is something Whishaw has avoided. Anonymity is key, he’s said in past interviews. “As an actor, your job is to persuade people that you’re someone else. So if you’re constantly telling people about yourself, I think you’re shooting yourself in the foot.”

It goes hand in hand with his aversion to the pursuit of fame over compelling art. “I think there can be an awful, heavy pressure to look a certain way, or be a certain thing,” he says. “Or fame. You could think that that’s what’s important when it’s not, really—at least it’s not for me, and it isn’t for most people I admire.”

But celebrity, whether sought or not, is a mercurial byproduct of such immense talent. If Whishaw’s current record of stage, television, and film roles are anything to go by, it’s a march toward the inevitable.