« Reply #329 on: November 09, 2017, 01:19:25 pm »

The ancient villa in North Italy almost outshines Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer.

TOUR THE 17TH-CENTURY ITALIAN VILLA

IN DIRECTOR LUCA GUADAGNINO’S

'CALL ME BY YOUR NAME'

The Lombardian Villa Albergoni propels — and rivals — the intimacy of

Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer in one of this year's richest films.

Luca Guadagnino likes houses. The 46-year-old Italian director has a history of lavishing homes in his films with the same love he gives his human characters. It could be argued that Guadagnino’s choice of Villa Necchi as the imposing temple of beauty in his 2009 masterpiece I Am Love was as important as his casting of Tilda Swinton. And 2015’s A Bigger Splash relies on the den of iniquity on the island of Pantelleria in which its protagonists pursue their misbegotten fates. The piano and slipcovered furniture in the Perlmans’ living room.

The piano and slipcovered furniture in the Perlmans’ living room. The remnants of a meal in the kitchen.

The remnants of a meal in the kitchen. The expansive vestibule of Villa Albergoni.

The expansive vestibule of Villa Albergoni. The exterior of Villa Albergoni.

The exterior of Villa Albergoni. Rumpled sheets in one of the bedrooms.

Rumpled sheets in one of the bedrooms. Elio Perlman (Timothée Chalamet) enters the Villa Albergoni vestibule.

Elio Perlman (Timothée Chalamet) enters the Villa Albergoni vestibule. Elio and Oliver resolve an argument with help from a statue's arm.

Elio and Oliver resolve an argument with help from a statue's arm. Elio and Oliver (Armie Hammer) bike to town.

Elio and Oliver (Armie Hammer) bike to town. A statue seen on a trip to an archaeological site in Lake Garda.

A statue seen on a trip to an archaeological site in Lake Garda. A clock tower in the the town of Crema.

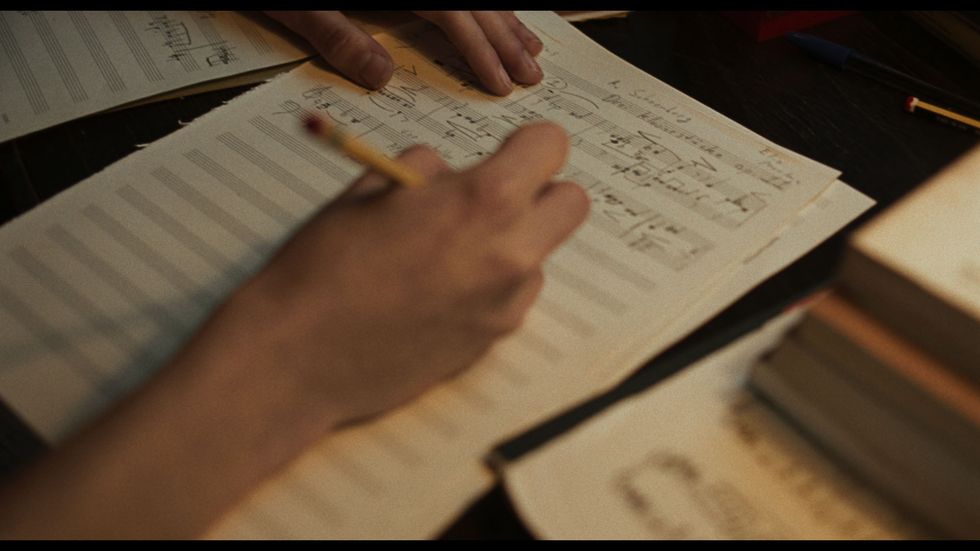

A clock tower in the the town of Crema. Elio transcribing a piece of music.

Elio transcribing a piece of music. The library of Villa Albergoni, site of the Perlman family home.

The library of Villa Albergoni, site of the Perlman family home.

And so the living room (whose original incarnation was, in Guadagnino’s words, “a sad and really uninteresting room”) became, thanks to Visconti di Modrone, an inviting repository. Italian by nationality but born in Singapore, she added a global influence, covering much of the furniture in Indian and Southeast Asian cotton fabrics (some from her own personal collection, and some from friends’ families whom she felt bore a resemblance to the Perlmans), including a cozy, blue and white–patterned example covering the sofa on which Elio and his parents curl up in a tangle of legs and arms for a reading one night. Elio heading downstairs.

Elio heading downstairs.

Maps from Perini and Piva also pepper Mr. Perlman’s library, an enveloping womb of a space that is, fittingly, the site of a pivotal scene in which father and son have a heartfelt discussion of Elio’s relationship with Oliver. Visconti di Modrone retained the space’s original dusty-rose sofa (“It gives the sensation of coziness and shabby chic that is right for the library — you feel that people stood and worked there,” she notes) but covered the walls in a gorgeous rust-inflected brocade from the fabric company Dedar, with whom Guadagnino also collaborated for his forthcoming horror film Suspiria. As a nod to Mr. Perlman’s profession, she layered the brocade with antique cameos of Lombardian kings and filled the shelves with flea-market tomes on Greco-Roman sculpture. Mafalda, the Perlmans' cook and housekeeper, in the kitchen.

Mafalda, the Perlmans' cook and housekeeper, in the kitchen. The aftermath of an alfresco meal.

The aftermath of an alfresco meal. The Perlmans’ gardener tends to a fruit tree.

The Perlmans’ gardener tends to a fruit tree. Oliver’s 1983 Converse sneakers at a disco in Moscazzano.

Oliver’s 1983 Converse sneakers at a disco in Moscazzano.

“The idea that a family like that would have a pool in a place like that was alien — it would have been nouveau riche,” notes Guadagnino of choosing an unconventional watering hole. “And I had a tragic pool in I Am Love.” Mr. and Mrs Perlman lounge outside.

Mr. and Mrs Perlman lounge outside.

“We tell stories, and those stories must happen in the space. Because we are not the product of, say, a piece of dialogue. The character must be a product of the behavior and interaction of the space,” explains Guadagnino. “So for me, space is everything.”

This story originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of ELLE DECOR.Also see:And see:

« Last Edit: November 09, 2017, 04:57:05 pm by Aloysius J. Gleek »

Logged

"Tu doives entendre je t'aime."

(and you know who I am...)

Cowboy Curtis (Laurence Fishburne)

and Pee-wee in the 1990 episode

"Camping Out"