The Worlds WithinTwo new shows celebrate Wassily Kandinsky and Georgia O’Keefe, diverse pioneers of abstractionReview by Richard Lacayo

in Time Magazinehttp://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1929214,00.htmlIt's been a long time since abstract art was a religion. For most artists now, it's just an option, a mode they can pursue or ignore as it suits them. But once it was a passion, a polemic, a faith. Wassily Kandinsky, one of its founders, could talk about geometric forms as though they were sacred images — and to him, they were. In a burst of high feeling he could argue, with a straight face, that "the contact between the acute angle of a triangle and a circle has no less effect than that of God's finger touching Adam's in Michelangelo." They just don't make triangles like that anymore.

By a happy coincidence of programming, two of New York City's biggest museums are looking back this fall on those exalted beginnings. "Kandinsky," at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, sends nearly 100 of the artist's works up the Guggenheim's spiral ramp like a whirlpool of angels in a Tiepolo ceiling.

Meanwhile, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, "Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction" scrapes away O'Keeffe's barnacled legend as the Gray Lady of New Mexico to recall the young woman who at the dawn of abstraction made a fearless leap into the unknown.

Like airplanes and antibiotics, abstract art is one of the defining inventions of the 20th century. But it's hard to say who arrived first at pure abstraction — images with no reference to the visible world — because abstraction is also one of those things, like calculus in the 17th century and photography in the 19th, that germinated in several places at about the same time.

In this case the time was the years just before and after the start of the First World War, in 1914. That was when the multidirectional Czech painter Frantisek Kupka and the austere Russian Kazimir Malevich were in their different ways achieving escape velocity on canvas. And so was Kandinsky, who would become the most tireless apostle of an art that answered to nothing in the merely material world. Born in 1866 to a prosperous Moscow family, Kandinsky spent his 20s studying law and economics, all the while bending toward another calling. He was the sort of young man who could be sent into ecstasies by a sunset. "The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot," was how he described one years later, "which, like a wild tuba, sets all one's soul vibrating." A wild tuba? So much for law and economics.

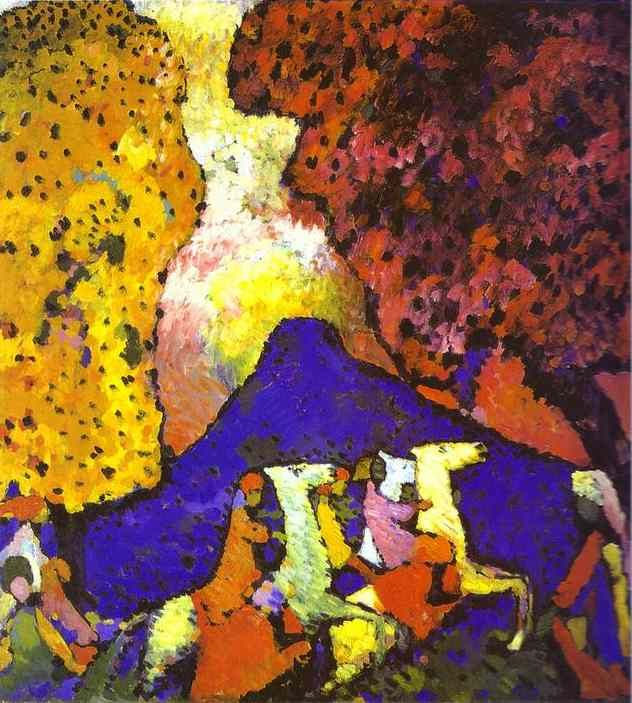

In 1896, Kandinsky, with his first wife Anja, decamped to Munich to become an artist and art teacher. His early paintings were folkloric, storybook scenes of an imaginary medieval Russia rendered like mosaics in bright lozenges of color. It wasn't until the summer of 1908, when he discovered the little town of Murnau in the Bavarian Alps, that he began to uncouple his pictures from any sources in the visible world. In Blue Mountain, which he began the following winter, he assigned the mountain an unearthly shade of indigo and turned the flanking trees into almost free-floating pools of pigment. With one eye on the crackling Fauvist pictures that Henri Matisse and André Derain had exhibited in Paris a few years earlier, he was on the way to letting form and color alone become the subject of his work.

Blue Mountain

Blue Mountain, 1908-09

En route to abstraction, Kandinsky embraced a more strident paletteFor Kandinsky, the horsemen in Blue Mountain had a symbolic meaning as emblems of expressive freedom. In 1911, when he formed an artists' group with Franz Marc, Alexei Jawlensky and a few other like-minded painters, they called it the Blue Rider. (Blue signified spirituality to him.) And by that year, with his succinctly titled Picture with a Circle, Kandinsky was galloping full speed in the direction of complete abstraction.

Picture with a Circle

Picture with a Circle, 1911

This may be Kandinsky’s first entirely abstract paintingBut for him, abstract images were also representations of a kind, correlatives of spiritual realities. He was an admirer of the Russian mystic Madame Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, a stew of beliefs about a spiritual realm that would someday replace the material world.

Helena Blavatsky

Helena BlavatskyThough Kandinsky's dedication to Theosophy is a familiar part of his biography, the Guggenheim show, which continues through Jan. 13, is largely silent on the matter. Has it all gotten to be too embarrassing? Without bringing it into the story, you can't fully grasp how Kandinsky, author of Concerning the Spiritual in Art, saw his work as a search for forms and colors that would speak the language of that higher plane.

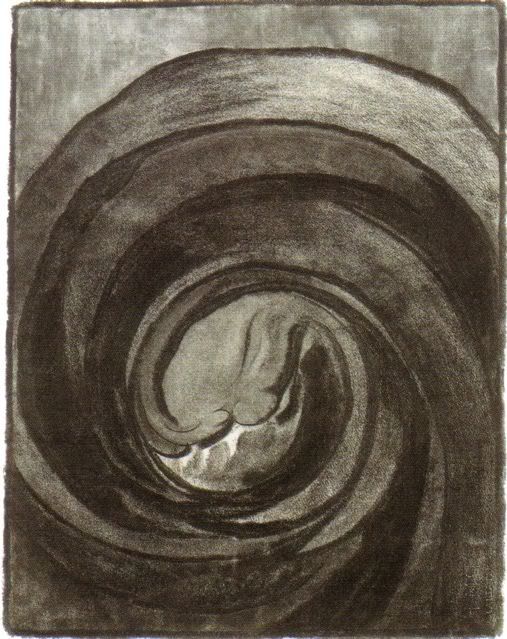

O'Keeffe, who owned a copy of Kandinsky's book, was no Theosophist, but like him, she felt that abstract art could express the artist's purely internal realities. In 1915 she was a 28-year-old art teacher stuck at a small women's college in South Carolina. One year earlier, she had been living happily in New York City and getting her first eager taste of Picasso, Braque and American modernists like John Marin. Stranded in a place she called the "tail end of the world," she decided to go where none of those artists had ventured. Drawing on the liquid forms of Art Nouveau and her own churning inner life, she produced an astonishing series of purely abstract charcoal drawings, some of the most radical work being done anywhere at that moment.

Drawing No. 8

Drawing No. 8, 1915

We would probably know nothing of those drawings today if O'Keeffe hadn't mailed some to a friend in New York who took them to the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, a pivotal figure in the small world of American modernism. Stieglitz agreed to include them in a group show at his 291 gallery, the tiny cockpit of advanced art where O'Keeffe had seen those Picassos and Marins. They were an immediate hit. Two years later, he gave her a solo exhibition that made her name for good.

By that time, O'Keeffe had reintroduced color into her work. Her typical canvases were eruptions of soft form, like the cresting fiddleheads of mauve, orange and green in Series I, No. 4, from 1918.

Series 1, No. 4

Series 1, No. 4, 1918

O’Keeffe’s oils drew from nature, Art Nouveau and her interior lifeBut she also worked in a taut, sharp-edged register that produced work like Red & Orange Streak, from the following year.

Red & Orange Streak

Red & Orange Streak, 1919

“I work in a queer sort of unconscious way,” O’Keeffe once wrote, “more feeling than brain.”Nothing about a picture like that suggests it's the work of a woman, but from early on, critics treated her paintings as bulletins from the Eternal Feminine. In her plump bulbs of color and shadowy openings they found the swells and inlets of the female body. Or as Paul Rosenfeld put it, "What men have always wanted to know and women to hide, this girl puts forth." Things got only worse after Stieglitz, who would become her lover and then her husband, exhibited his intimate nude photographs of her in 1921, pictures that marked her forever as the pinup girl of the avant-garde.

Let's grant that a lot of O'Keeffe's work invites those readings. When you're faced with the labial purple coils of a painting like Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, from 1918, what else can you think about?

Music, Pink & Blue No. 2

Music, Pink & Blue No. 2, 1918

Voluptuous works like this led people to misconstrue O’Keeffe’s full intentionsBut what's so refreshing about the Whitney show — which runs through Jan. 17, then moves to Washington and Santa Fe, N.M. — is the way it spares us O'Keeffe the Earth Mother and points us back to the endlessly inventive formalist she remained, intermittently, to the end of her life.

Abstraction may not be a religion anymore, but you can't look at the early buoyant pictures in either of these shows without being glad that, for a while, there were artists who kept the faith.